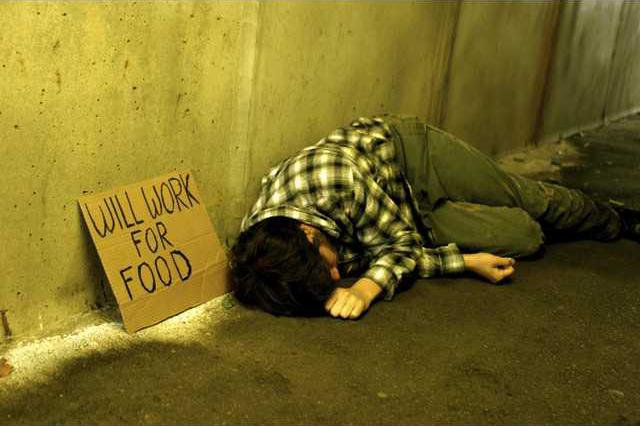

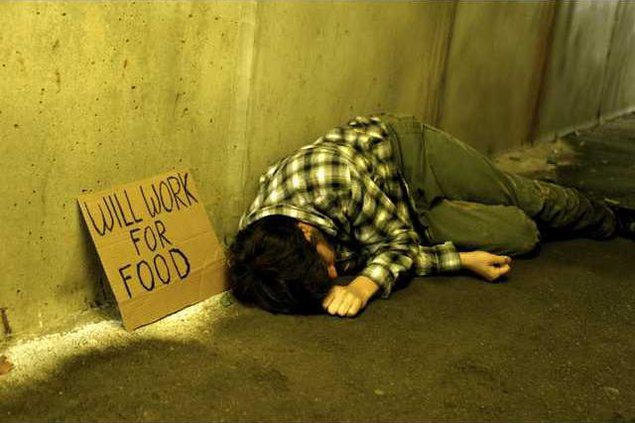

Tom Rebman, a 53-year-old Florida middle school teacher, spent a month living as though he was homeless. He took on the project, he says, to raise awareness for a local food bank and to inspire the kids that he works with.

He wouldn't have gone through with it, though, if he had known how hard it was going to be. "I thought it was going to stink, but it would be bearable," says Rebman. The reality? "It was hell."

The former navy vet, who came home last week after a month on the street, says that trying to get by as a homeless person was the hardest thing he has ever done — and now he's an advocate for the homeless people that he met firsthand. Rebman talks to us about the realities of living on the street — sleepless nights, hunger and constant fear — and busting the myths of homelessness.

Question: What did you think being homeless would be like going into it?

There is a homeless camp a quarter mile from my house, and I imagined that it would be like sleeping in the woods and getting bit up. But I would get a tent and make a little money just walking around cutting people's lawn for $5 if I couldn't get a job. I thought it's going to suck, but it will be bearable.

The reality was I kissed my wife goodbye one night and took nothing but my cellphone and driver's license. I wandered four miles before I found a safe place — and I slept on a park bench. I woke up at 3:30 in the morning because someone had his hand in my back pocket trying to steal my wallet, and it was downhill from there.

Question: Were you able to make any money from panhandling? There is a notion that panhandling can be lucrative

When I panhandled in traffic where there are cars, I was averaging $16 to $18 an hour. The problem is that's not legal in many places — and it's not in Florida. So police moved me to a "designated area" where panhandling was legally allowed. There I made about nine cents an hour standing in the sun.

I can't say what it's like in other cities, but If I was to guess I'd say that about three percent of panhandlers are making money and 97 percent suffer.

Question: You made many friends on the street that you still keep in touch with. Was your impression that many of them suffer from mental illness?

If you do not have mental issues when you are first homeless, then you almost certainly will develop them. If you were a normal citizen, I assure you that within 30 to 60 days in you’d have PTSD symptoms. I know that's what it felt like for me, and I was in the military and had PTSD issues in the past and felt similar symptoms. It's mentally unbelievable. In Florida you're out all day in 100-degree heat, you never stop sweating, you don't get a shower for days. I sneaked into an Embassy Suites swimming pool to wash off. I slept 3-4 hours a night because you're constantly afraid of getting caught and arrested.

Question: You say that you were turned down for work hundreds of times, and you were able to make money by selling your blood plasma. How often did you go hungry?

I went hungry a lot, and when you get hungry enough you will panhandle legally or illegally. You'll consider dining and dashing. You get so hungry you don't care if you get caught. That happens after about 12 hours with no food. Everyone should try it sometime.

Question: Did you start to see non-homeless people differently — people like yourself?

When you do earn a dollar for a cold bottle of water or a crappy pack of cigarettes — just the $2 cigarettes — you go to the 7-Eleven. You can't bring your stuff inside, so you're freaking out the whole time that it will get stolen. And everyone is looking at you like you're a leper. Then, the guy in line in front of you whips out two $50 bills and buys scratchy cards and I want to punch him in the face, though I wish I wouldn't feel that way.

That money would feed me for a week and a half. I could get a hotel room, a shower, watch TV. It's not rational — I know it's his money and he's done nothing wrong. But the hardest part is the mental anguish — the constant suffering. It's demeaning.

Question: What about shelters? Could you find a safe place to stay there?

I went to a local shelter and the first thing that I had to do was give them all my clothes so that everything could be washed. I sat in a chair in a smock for seven hours because it was so inefficient. Because of crime within the shelter, the lights don't go out at night. Sometimes it's safer on the street. There was also a book of rules that was a quarter inch thick — so it was easy to get in trouble. The rule book is written at about a 10th grade level — and I would know, because I'm a reading teacher. I have a degree and I had a hard time absorbing it, so I can imagine how it was for others.

The rules also made it hard to work. I offered to help a guy clean his bar and he said to come back after closing at 2:30 a.m. and I'll give you $40. Well, the curfew at the shelter was 11 p.m.

Deseret News: You say that you were grateful for anything you got from strangers — food or money. But there's a common concern that that money goes to drugs or alcohol.

There is less drug and alcohol abuse on the street than in mainstream social life. This is largely because homeless people don't have the money to buy it. It seemed to me that the number of drug abusers that I came across on the street was about 10 percent. Do the homeless get drunk? Yes — when they can. But not as much as regular people. Unfortunately, the drunks on the streets are easy to see.

Question: How do you feel about giving money to people on the street now?

I have changed my philosophy on that. When I was helping feed the homeless in homeless camps, I refused to give them money. I didn't want to be responsible for their drinking or their crack. Here's how I look at it now: As much as they suffer, who am I to tell them how to spend the money that I give? I'm not saying that I condone that behavior — I don't drink myself. The point is that what they need is money.

Email: laneanderson@deseretnews.com